Water and wastewater treatment plant projects in Kentucky have historically progressed at a trickling pace.

Water and wastewater treatment plant projects in Kentucky have historically progressed at a trickling pace.

Just ask Warren Rogers, who spent three decades as owner/president of W. Rogers Company in Lexington building water and wastewater treatment plants in the commonwealth before selling the company in 2016.

During Rogers’ tenure, WRC built more than 300 facilities in 62 of Kentucky’s 120 counties. Time and time again, he saw projects for which his company bid or was the successful bidder be over budget, scaled down, postponed or not awarded at all.

Why? A multitude of federal regulations drove costs up over the course of the projects’ conception to completion, a process that could take as much as a decade even for simple projects in a moderately sized community, Rogers said.

Fundraising was performed around initial budget figures, he said, but by the time bids were awarded, those figures often had become outdated and the project would appear over budget from the start, necessitating hard decisions to bring the dollars back in line.

“Not every project was that way, but many certainly were,” Rogers said.

Projects often rely on limited federal funds administered by the Kentucky Infrastructure Authority (KIA) through Area Development Districts, but that can be a waiting game.

A glance at KIA’s online Kentucky Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Planning Dashboard shows total funding needs of more than $5.9 billion. Of 5,599 total projects in Kentucky communities—3,329 water and 2,270 wastewater—2,331 have been constructed, 3,044 are listed as pending or approved, and 224 are in the construction phase.

Rogers wondered if there was another way for these projects to proceed, and began working with others to draft an update for Kentucky’s Public Private Partnership (P3) law HB309, enacted in 2016.

It allows local government entities to partner with the private sector and include financing to bring projects to fruition—often in a shorter time frame and without budget shortfalls from inflation that typically occur when timelines lag.

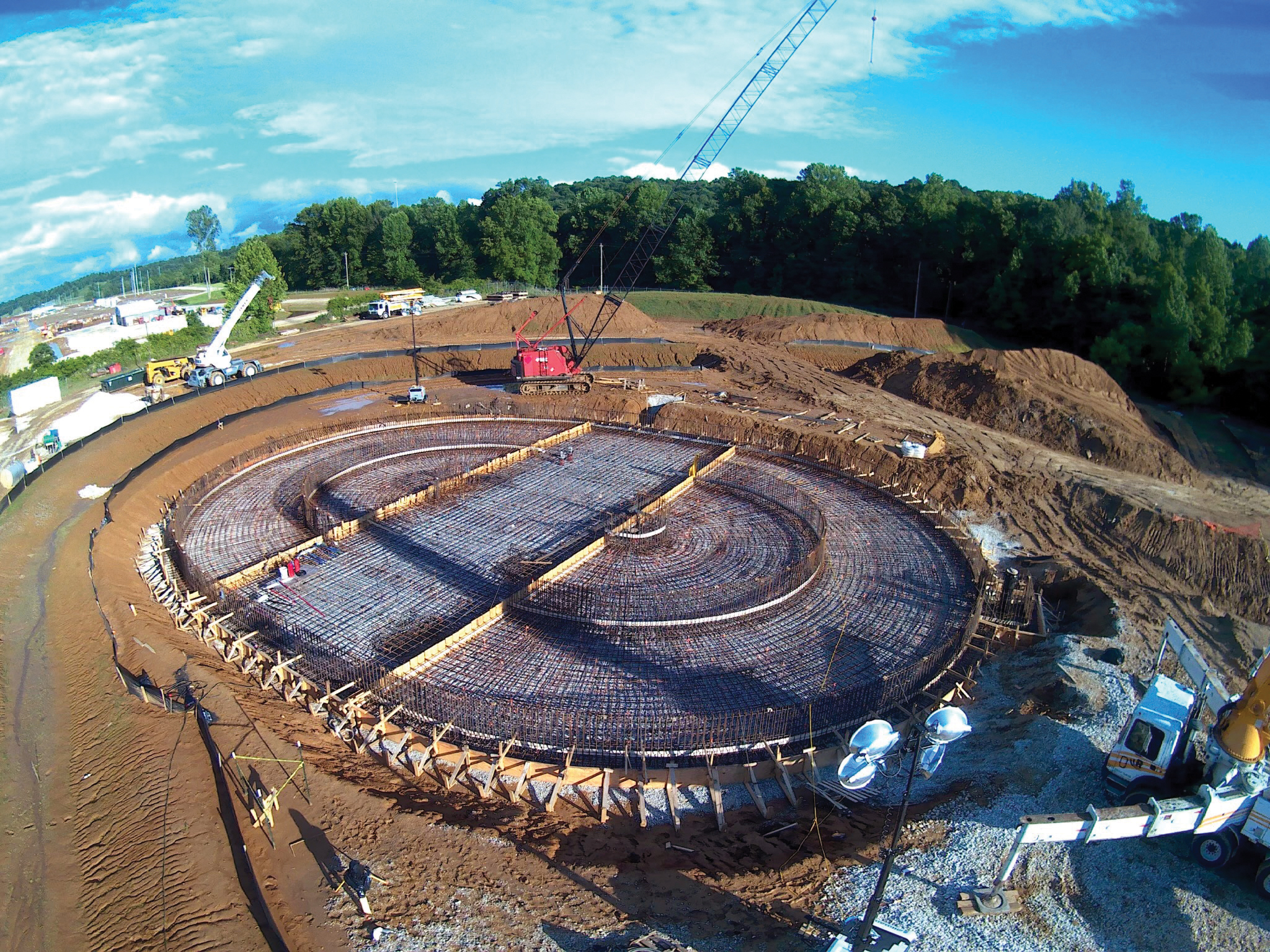

The first local project to use this method broke ground in February 2021, an $8.3 million wastewater treatment plant in Brandenburg.

“Brandenburg had a serious need,” said Brandenburg Mayor Ronnie Joyner in a news release for the groundbreaking. “We had to build a new wastewater treatment plant that could handle not only the present but also the future needs of the city. We needed to explore all of our options to find the quickest and most cost-effective way to build this plant.”

Legal firm Frost Brown Todd served as project consultant, issuing a P3 Request for Proposals to design, build and finance the plant, receive innovative solutions, negotiate the agreement and facilitate regulatory approval processes.

Ultimately, Mount Sterling-based design and construction firm The Walker Co., partnering with GRW Engineers and WP3 Consulting, was selected as the design/build contractor, with Ross Sinclaire & Associates providing financing in partnership with Kentucky League of Cities Financial Services and the Kentucky Bond Corp (KBC).

The parties’ process and agreement was later unanimously granted the first approval of its kind by the Kentucky Local Government Public-Private Partnership Board. Brandenburg and Meade County each fund half of the project, with KBC issuing bonds.

Significant among the future needs the new wastewater treatment plant will meet are support of a $1.7 billion steel plate manufacturing mill Nucor Corp. has under construction in the Buttermilk Falls Industrial Park, land that includes Brandenburg’s existing wastewater treatment facility. That project—one of the largest in Kentucky history—broke ground in October 2020 and will create an estimated 400 new jobs. Rogers, now managing partner for WP3 Consulting, began exploring local-level P3 possibilities in 2013, eventually gaining support of construction associations in the state, the Kentucky Chamber of Commerce and others.

A P3 coalition made up of approximately 40 members formed and met regularly to help the effort gather momentum, with Rogers as chairperson. Members represented government, industry and other stakeholders and worked together to draft the bill that was sent to the state House of Representatives in 2015 before being vetoed by then-Gov. Steve Beshear.

The measure resurfaced with tweaks in 2016 that included the local government P3 portion. After successful passage by legislators it was signed by then-Gov. Matt Bevin in April 2016.

J.D. Chaney is executive director/CEO of the Kentucky League of Cities and was involved in crafting the local government portions of the updated legislation.

“What the legislation did in 2016 was create a streamlined mechanism and establish a blueprint that local governments could use under the law, knowing that statutorily it was an authorized procedure,” Chaney said.

“What the legislation did in 2016 was create a streamlined mechanism and establish a blueprint that local governments could use under the law, knowing that statutorily it was an authorized procedure,” Chaney said.

Once local governments see local P3 projects in action, he expects other project applications will be explored, whether it’s water or wastewater related, a convention center or other community recreation projects. It may also be looked to as a good template for other states wanting to target local P3 projects, he added.

The Walker Co. CEO Jake Schirmer said his company was awarded the bid for the Brandenburg wastewater treatment plant project on Sept. 30, 2020. His firm received a limited notice to proceed for design and limited site work in January and by early June 2021, construction was already 20% complete. The estimated completion date is June 30, 2022.

Schirmer said this timeline is much faster than the typical design, bid, build model, in which the design phase could take a couple of years, followed by a four- to five-month bidding process, all while trying to secure financing and factoring in a few years for construction. All told, such projects commonly take four to five years.

“In the P3 model, it’s really unique because the municipality put out for bid the need for a wastewater treatment plant and we came up with our own design and we were awarded the job based on our qualifications and what the best overall value was for the municipality,” he said.

Schirmer said that based on a 2 to 2.5-year time savings using the P3 model, inflation and the $8.35 million project cost using a third-party financial group, he estimates a cost savings of about $3.5 million.

He said to learn more about local P3 projects, municipalities typically look to KLC and Kentucky Association of Counties resources, and representatives with his firm are also willing to lend advice.

Casey Bolton is partner with Commonwealth Economics, a Lexington-based firm that conducted a financial feasibility study for the Brandenburg project. This analysis is required by statute to see if the P3 delivery model is best suited for particular projects or if the traditional process should be followed, he said.

Bolton said the language on financial feasibility in local P3 statutory regulations is quite in-depth. It examines whether a given project will work under the P3 format from a timing, fit and savings standpoint.

He said in a local P3 agreement, those involved can not only determine arrangements for building a facility with protections built in for each party, but agreements can also include engaging private-sector companies to perform operations, building maintenance or other services.

“It’s really a great tool to leverage private-sector expertise to come up with creative ways to find solutions to public needs,” Bolton said.

Leslie Combs is a former state representative from District 94, who helped craft and lead all aspects of HB 309. She also formerly served as executive director of Kentuckians for Better Transportation.

Combs said she’s excited about the Brandenburg project, as using the local P3 framework provides municipalities new ways to raise revenue using private-sector capital.

“It’s probably the only way that, in my opinion, local governments can get the much-needed infrastructure that they really need …. They don’t have the resources and they don’t have the borrowing capacity,” she said.

Combs said some may initially have feared the plan sounded too good to be true or that there had to be a catch, but she’s confident the thinking behind the legislation was thorough, fair and resulted in a “good, longstanding product.”

For instance, she said, local governments can even enter into long-term arrangements with the private sector to maintain and repair 100 bridges in a designated area for 30 years, using existing transportation funding to provide a guaranteed annual payment to the contractor.

If a contractor were to go out of business during that time, their remaining obligations would be addressed in the agreement.

“This is designed to take what ability you have to pay and match it up with your need,” Combs said.

Rogers said the local P3 legislation encourages collaboration and out-of-the-box thinking. In addition to individual city and county projects, it can be used for regional projects with multiple counties involved.

Rogers said he meets with many public officials and people in the design community and tells them that the P3 method will save time from concept to completion and save significant dollars during the overall process.

“The great thing here is you can use creativity and common sense that entrepreneurs like to utilize to get problems solved, to get things done,” he said.

Shannon Clinton is a correspondent for The Lane Report. She can be reached at [email protected].

Click here for more Kentucky business news.