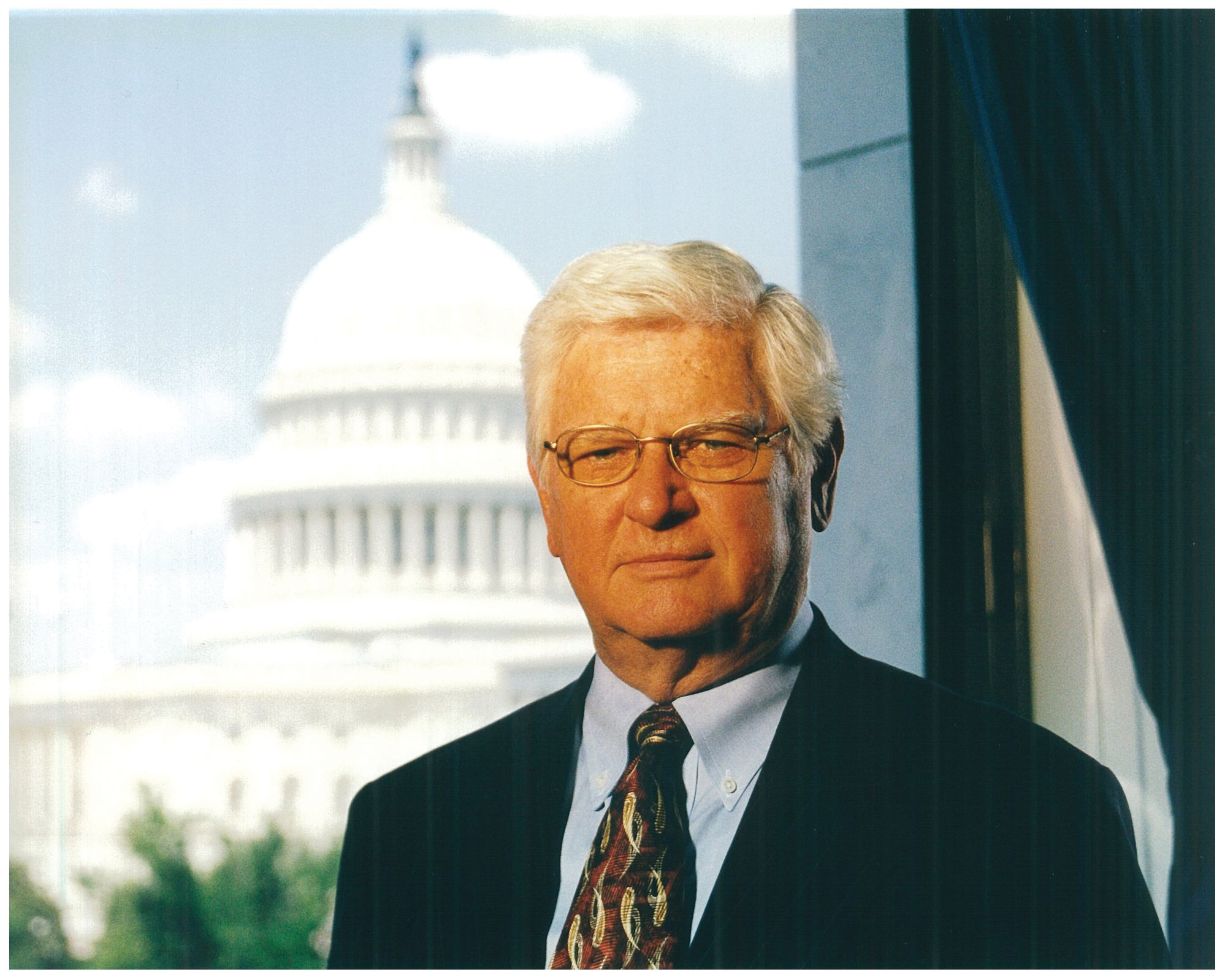

Hal Rogers has a long history in Congress—at 42-plus years he’s “Dean of the House”—but has an even longer history in Kentucky economic development. His efforts have made a positive impact on the lives of millions in his southern and eastern Kentucky district and beyond.

Hal Rogers has a long history in Congress—at 42-plus years he’s “Dean of the House”—but has an even longer history in Kentucky economic development. His efforts have made a positive impact on the lives of millions in his southern and eastern Kentucky district and beyond.

Years before first winning election to Congress in 1980, Rogers inadvertently passed on getting in at the launch of the Kentucky Fried Chicken empire because rather than move to Louisville, he preferred to play a role in improving life in his home region.

Both John Y. Brown Sr. and John Y. Brown Jr. needled Rogers many times about his choice over the ensuing years, he said, but it has worked out well for the man who chose to join a Somerset law firm and went on to bring billions of dollars in life-improving projects to Eastern Kentucky. And he isn’t finished.

Motorists can travel the 91-mile Hal Rogers Parkway from Somerset to Hazard, but other more significant infrastructure projects and initiatives bear his imprint or exist due to his efforts in Washington to get them in the budget and—perhaps more importantly—funded.

Among those projects are the Cumberland Gap highway tunnel; floodwalls and rerouting of the Cumberland River that ended annual flooding for communities; expansion and improvement of major highways; construction of a statewide broadband network with nodes in all 120 Kentucky counties; creation of the Southeast Kentucky Economic Development Corp.; The Center for Rural Development; four federal penitentiaries; instruction for companies on becoming federal contractors…

These are just some of the billions of dollars in economic impact U.S. Rep. Hal Rogers has worked with intention to create for southern and eastern Kentucky. There will be more since he has just begun a 23rd term in office by being appointed chairman of the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice and Science, with oversight of NASA, the International Trade Commission, the Department of Commerce and the Department of Justice.

And after catastrophic flooding last summer in many Kentucky River valley communities that are part of his district, Rogers has begun efforts to provide that watershed with the same improvements that were achieved along Cumberland River communities.

The Lane Report spoke with Rogers recently about the economic development priorities he has pursued during his time in Congress. This is a lightly edited transcript of the interview:

Mark Green: You are now dean of the United States House of Representatives with 42 years of service and counting. When you were first elected, did you have expectations of a long tenure?

Hal Rogers: No. As I look back on it now, I’m surprised that we’ve persevered this long. I had no expectations of the long tenure when I first won the seat in 1980.

MG: Why and how did you enter politics?

HR: I was influenced in a big way by my brother-in-law, Lloyd Tatum from Tennessee. He married one of my sisters. He was a lawyer in Jackson, Tenn., and I greatly looked up to him in any number of ways. He was my inspiration to go to law school, become a lawyer. And then down through the years he advised me in all my life and all the activities that I’ve been involved in.

He encouraged me in politics and over a period of time, I came to think about politics as a way to improve the lives of people in this part of Kentucky. He was active locally, helping others, and then eventually he was a member of the Tennessee Supreme Court. He was an advisor all of my political life. Economic development was a part of my attraction to politics as a way to achieve a better way of life for my fellow citizens.

When I graduated from UK law school in ’64 I had to decide what to do. I had been clerking for a very well-known lawyer at the time, John Y. Brown, and he liked the work and research I was doing for him. He was a great trial lawyer. He wanted me to work for him out of school and move to Louisville and open a branch law office with John Y. Brown Jr., who at that time was selling encyclopedias. I thought about it very seriously, mulled it over. In the meantime, I got an offer from a law firm in Somerset, which I chose because I wanted to come to my home region and work in economic development to find jobs and a better way of life for people. I turned down John Y. Brown Sr. and Jr. It was shortly after, of course, that Junior founded the world’s biggest food franchise, Kentucky Fried Chicken. I’ve often thought, boy, had I done that I’d have come out really well. They both would tell me every time I saw them, “Boy, did you make a bad mistake!”

MG: When people come to you and say they are interested in getting into politics or public service, what do you tell them? HR: I tell them to study history, to study hard on all aspects of life and to get active in others’ campaigns, learning as you go, building as you go. Be active civically and make a lot of friends along the way.

HR: I tell them to study history, to study hard on all aspects of life and to get active in others’ campaigns, learning as you go, building as you go. Be active civically and make a lot of friends along the way.

MG: Do you encourage them to get in or do you give them warning?

HR: I give them encouragement. I point out that along the way it’s gonna take a lot of work and sacrifice of your private time, but it’s a worthy and noble calling.

MG: In addition to your brother-in-law, have there been other important mentors, counselors or advisors?

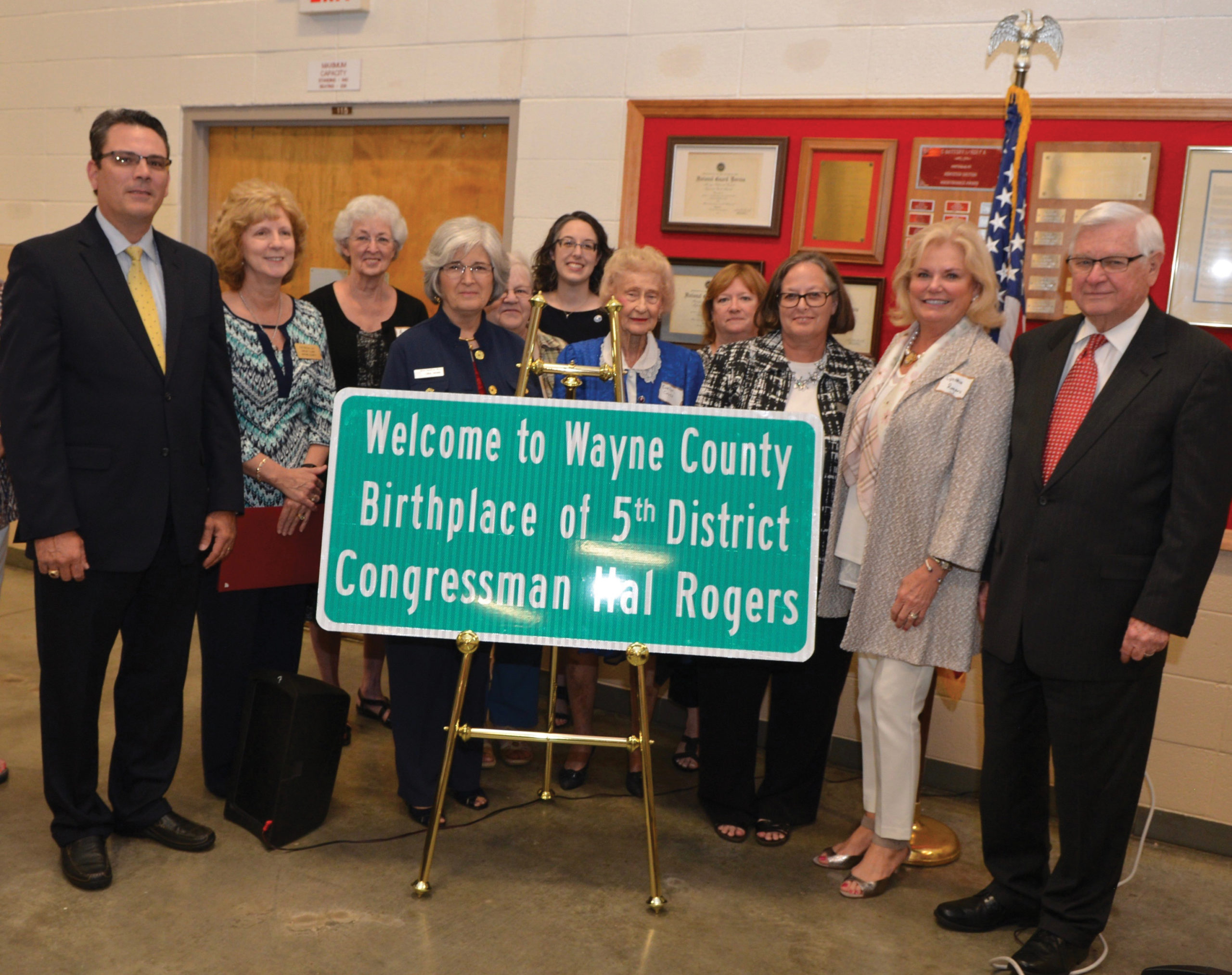

HR: That’s a long list, but I’m thinking my eighth-grade teacher at Wayne County High School, Clarence Bates. Later he was superintendent of the Wayne County schools. He was a big influence on me. I’m very active politically in Wayne County. And I dare say any Kentuckian would tell you that one of their inspirations was Sen. John Sherman Cooper; that was true of me. And, my predecessor, Congressman Tim Lee Carter, who served 1965-1981. These were people who inspired me along the way. And there were people in my campaigns and in office, like Doris Petercheff from Pulaski County, who was Tim Lee Carter’s district administrator; she was very instrumental in my early political ventures in every way. Marty Dreisler was my finance chairman when I first ran and then became my D.C. chief of staff; very influential and smart. Of course, I can’t leave out Judge Roscoe Tarter, who was a circuit judge here in Pulaski County and was Cooper’s uncle; he helped me in my early career.

There are people of late like all of my staff along the way, there (in Washington) and here, and especially my good colleague from Oklahoma, Tom Cole, who still remains one of my big advisors and confidants.

MG: You have a long list, but what have been your most satisfying accomplishments as a congressman?

HR: I’ve been very pleased over the years with bringing fresh water to communities who have been lacking it. When I first took office, only 40% of the residents (in the 5th District) had “city” water. Now that’s upwards of 90%. That’s very satisfying. And then the flood protection, especially on the Cumberland River all the way from Letcher County down to the Cumberland Falls, where they perennially flooded. Pineville, for example, Williamsburg, Harlan and so forth; all of those towns would flood almost every year. My first weekend in office I had the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers helicopter us along the Cumberland River; I wanted them to point out to me what and where they could make a difference if they had the funding. We flew the length of the river and came up with those separate projects, like in Pineville—which was the first one—for a flood wall and protection. In Harlan, we rerouted the Cumberland River around the city of Harlan as well as building levies. Then Williamsburg, the same thing; and Barbourville, same thing. Those towns no longer flood. I’ve been extremely pleased to see that protection for people, to protect their homes and their churches and saving their family Bible, for example, from the floodwaters.

And then early spotting of the opioid outbreak, which got its start in my district with OxyContin. We started an organization called UNITE—Unlawful Narcotics Investigations Treatment Education—that went to work in my district maybe 15 years ago now. It is still going strong. In fact, we took that model that had proved successful here and took that nationally and started an annual summit on opioid overdose deaths. Thousands of people from all over the country come and take part; these are the nurses and lawyers and prosecutors and sheriffs and state police and so forth. Every president has attended that summit and hopefully will again this coming April.

And then PRIDE. We had a lot of trash and litter and filth in our streams and across the mountains, so we started the PRIDE program—Personal Responsibility in a Desirable Environment. That has consisted of thousands of people picking up trash and cleaning up rivers, taking cars and refrigerators out of streams. For example, they’ve pulled from the creeks and rivers almost 1 million tires and 170,000 refrigerators and bathtubs, big pieces. That’s been a national winner as well.

Then lastly, when we lost the coal industry, I set out to try to find a substitute. I lined up with then-Gov. Steve Beshear and started an organization of volunteers called SOAR, Shaping Our Appalachian Region. That’s ongoing and growing by the day to find new ways to make a living. We focused on taking broadband to every community, every county. The governor wanted to expand it to the rest of the state and I agreed, so we try to find funding and interest. We’ve had summits every year and that group is paving new trails and using the newest technology like broadband to create new types of jobs in Eastern Kentucky. I call that effort “reaching into silicon holler.”

MG: Is there a disappointment? An issue you have tackled that didn’t achieve the result you hoped or that you still feel the need to take on?

HR: Flooding. This last enormous flood was mainly in the valley of the Kentucky River, which has not been a part of our district until here lately. That flood was the largest ever and the most destructive. I’m asking the (U.S. Army) Corps now to do what we did on the Cumberland; let’s look at the entire Kentucky River basin to see how we could—if they had the funding—stop the flooding on the Kentucky River much the same as we did on the Cumberland. That’s ongoing. Beattyville, they’re now developing the project there, for example. But we’re also doing floodwalls in Paintsville, working along the Big Sandy River to elevate homes out of the floodplain, for example, and finishing up the relocation of the town of Martin in Floyd County, where for the last dozen years we’ve been carving up a mountain to make room for the new town of Martin and then moving the old town up to that new level out of the floodplain. It’s a big, fascinating project.

MG: You have special insight into Eastern Kentucky economic development. What potential or ongoing efforts will make the most positive difference?

MG: You have special insight into Eastern Kentucky economic development. What potential or ongoing efforts will make the most positive difference?

HR: One of the biggest assets we have is the quality of the workforce in the mountains. With the demise of the coal industry, we have a lot of trained, experienced workers waiting for a job. Different companies around the country tell me that the potential our workers have is the best resource we have. Those companies tell me that the quality of our workers exceeds any they have in the rest of the country, so I know we’ve got a winner. The broadband project (Kentucky Wired) is an effort to put that special workforce to work. I think broadband is probably the best possible way to develop economically in Eastern Kentucky.

MG: You’ve been instrumental in major infrastructure projects during your time in office: the Cumberland Gap highway tunnel and improvement of the Mountain Parkway, the Kentucky Wired broadband project. How do you characterize the impact of these events over time? And are there other major infrastructure projects that you hope to see become a reality?

HR: On the Cumberland Gap tunnel, the U.S. 25 E highway runs through Bell County and others and part of that highway had to cross the Cumberland Gap on U.S. 25. There had been any number of people killed traveling over that very curvy old road. In fact, that was the original Boone trail that Daniel Boone founded (Wilderness Road, created in 1775). It was the way they crossed the mountains, but it was a major problem for accidents. We went to work to see if there was a way to fix the problem. The engineers suggested that tunnel under the mountain; taking 25 E across the mountains out of business and running it through the tunnel and solving the accident phenomenon. And it’s worked. When we opened that tunnel (in October 1996), the traffic on U.S. 25 doubled overnight, and it’s still doing that. Then we restored the old highway, the old 25 E route across the mountain, to the way it was when Boone came through. It became a good tourist draw. I’m very proud of that tunnel.

Improving the Mountain Parkway has been a project over the years that we worked with the state to improve. We’re making great progress on it and I want to see that all the way through.

And then the Kentucky Wired and the Center for Rural Development in Somerset, which I have found the money to build; it houses all of these different civic activities that I’ve mentioned so far. Sonny Lawson, the head the center, was high on broadband, so we took that project on to wire our district. And along the way the governor, Steve Beshear at that time, wanted to join in and run it statewide, not just in east Kentucky. I told him, “OK, if you got the money, I’ve got the time.” That was the birth of Kentucky Wired. It’s now in every county in Kentucky, and we’re trying to run it as quickly as we can from the main highway, the main wire, into every community. I think that’s our future, Kentucky Wired.

MG: What issue or issues does the Kentucky business community come to you about most often?

HR: Tax reform, tax reduction, and then the overregulation by the government. Those two fields of complaints exceed all others. There are more federal agencies that I think in many cases exceed their authority, and it takes congressional activity to back them down, so I’ve been active in that over the years.

MG: One of your initiatives has been to help Kentucky companies become qualified as federal contractors. How do you characterize your success at getting that done?

HR: I started a thing called SEED (Supplier Education and Economic Development) that is an effort for local businesses interested in becoming competitive for federal contracts. We put on seminars here in the district every year where we bring in federal contractors like Boeing and Lockheed Martin, the big companies, federal contractors. They send their representative here and bring in the local businesses that are interested in becoming federal contractors. They spend two days together with hundreds of our participants. The goal of the SEED symposium is to make sure that our companies are in the race for those jobs, that those contractors are qualified.

It’s been very successful; we’ve had several hits. I am thinking of Rajant (Corp., mesh wireless communication technology provider). In fact, I recruited Rajant myself. They have a fascinating new way (of operating) that we need to look at in our region to duplicate. They wanted to come to Kentucky, and we showed them around. They liked Morehead, where they have since built some buildings. They’re working with Morehead State University, which is another story.

Several years ago, the president of Morehead State came to me asking for a grant to buy a huge used satellite dish; it was some 68 feet across. We were able to get that for them; it’s on top of the mountain overlooking Morehead now. It was also the seed out of which the university started a space science degree. Today they’re hiring the graduates of that school at Rajant, because that’s what Rajant is involved in. The students at the college and Rajant in Morehead are building satellites, seeing to the launching of that craft, monitoring it in orbit. That dish was the starting point for it and is now one of four NASA tracking stations around the world. That is a fascinating new way of looking at life and Rajant is hot to trot for it.

There’s also Outdoor Ventur eCorp. (in Stearns) that makes a lot of military equipment. Dajcor Aluminum (in Hazard supplies extruded and fabricated components). Lincoln Manufacturing (in Stanford supplies precision metal components) and so on.

These companies have received seed grants through the Appalachian Regional Commission POWER program, created around 300 jobs and invested around $30 million in our region. Certification is a long process for all companies. We’re proving that we can compete for federal contracts. We can do the work right here in southern and eastern Kentucky.

At the symposiums, these local companies set up displays in the Center for Rural Development. It’s amazing to see what’s already being done here through that SEED program. It’s working and it’s working well and it offers us new opportunities.

MG: People like to say nothing gets done in Washington. Things do happen but more slowly than most of us want. Two questions: Are people’s expectations a little unrealistic? And if Hal Rogers could make changes in the congressional rules to improve outcomes, what would that be?

HR: Boy, where do I start? We don’t realize it, but when our founding fathers wrote the Constitution, they wanted to make it difficult for the federal government to become too powerful. So they made it very difficult to pass laws. That’s not a bad idea, but it also makes it hard and takes more time to get a solution to a very evident problem. The government was designed that way. And if we could change it, I’m not sure where I’d want to go.

MG: The business community always wants better clarity on what to expect so they can make plans to grow or invest or just adjust for what might be coming next. Can you offer any advice on tax policy, regulatory policy, the economy or major trends you see?

HR: I’d like to see the federal government find ways to say yes and to stop always looking for a no. Businesses need to be encouraged with tax policy and regulation policy and the like. I think attitude has a lot to do with it. That means presidential politics and presidential activities and attitudes. We find that the policies of more liberal federal government are slow to help businesses rather than trying to find ways to help them.

MG: Can you give them any advice on how to plan for 2023 or 2024?

HR: I would like to think that more conservative policy out of Congress and, more importantly, out of the administration is likely.

MG: What does a member of your experience understand about government and public policy that new members do not?

HR: It takes a lot more patience and perseverance than they first thought. It is a place where the partisan divide is alive and well. That makes it especially difficult to put together a majority to pass a bill. I think they have to understand that it takes time and it takes hard work, both in Washington and back in their home districts, so be patient.

MG: Do you have any advice that would lead to a lessening of the partisan divide that we have nowadays? HR: Unfortunately, I don’t see that happening. We have a very severely divided Congress and country. It’s going to take especially hard work to find those in Congress that want to see the country proceed and succeed. That’s going to be tough to do given the narrow margin that Republicans will have in the House.

HR: Unfortunately, I don’t see that happening. We have a very severely divided Congress and country. It’s going to take especially hard work to find those in Congress that want to see the country proceed and succeed. That’s going to be tough to do given the narrow margin that Republicans will have in the House.

MG: Do you have any closing statement?

HR: No. 1, I thank you for The Lane Report. It’s a great piece of work, helpful to businesses large and small. It’s been a great honor to represent the people of Eastern Kentucky in the U.S. Congress. It’s been a long, hard slog. Our district has been hit time and again with natural and unnatural (events). We lost the timber industry over time. We’ve lost most of the coal industry. We lost tobacco. And then we have had a lot of flooding and fires and the like. We’ve had more than our share of difficulties to overcome. There are profound differences, but I want to thank the people of Kentucky for supporting me over these years and I hope to satisfy them.