Mark Green: Why do we need hospitals specifically for children? What is the difference in approach if patients are children?

Dr. Scottie B. Day: It’s important to have not just the equipment with the staff and training. Children are not small adults. From the young age of a baby all the way up, there’s very specific equipment but also nursing care, pharmacy care, physicians. It’s a very specific facility to allow you to take care of the baby that’s a day old all the way up to a teenager.

MG: What are some of the differences as you’re approaching these smaller patients?

SD: In the equipment, the ventilator you need for a small baby is very different than that of an adult. The pharmacy is key to much of what we do and the dosing is different for a 3-kilogram baby versus the 20-kilogram (child) versus a 30-kilogram (person). There are respiratory things. There are dynamics in the lungs of a child that are very different. Even within the children’s hospital there’s a big difference between the neonate, the babies just born—whether it be premature, which is important in their lungs—versus a child that’s a little bit older. Now children are living longer lives; we don’t talk a lot about mortality in children because in general children with chronic illnesses can live long lives now. And how you approach those children is important, and the ability for us to do that is key and part of our mission.

MG: What are the differences in education and training for medical personnel and providers who specialize in treating babies and children?

SD: You have your core pediatric knowledge and general information piece, but even within pediatrics there’s very different training. I was trained as a pediatric ICU doc, so I had specific training related to taking care of critical-care babies all the way up to teenagers. It could be from a child with congenital heart disease all the way up to a teenager in a trauma. We’re not just specialized in children. A lot of times we’re specialized in children with specific diseases, children with pediatric cancer, children with diabetes, children with GI issues. Those specific trainings are not just for the physicians and the nurse practitioners or the physician assistants; they go all the way down into the staff. I can’t emphasize how important it is for our staff to know how to start an IV in a 500-gram baby.

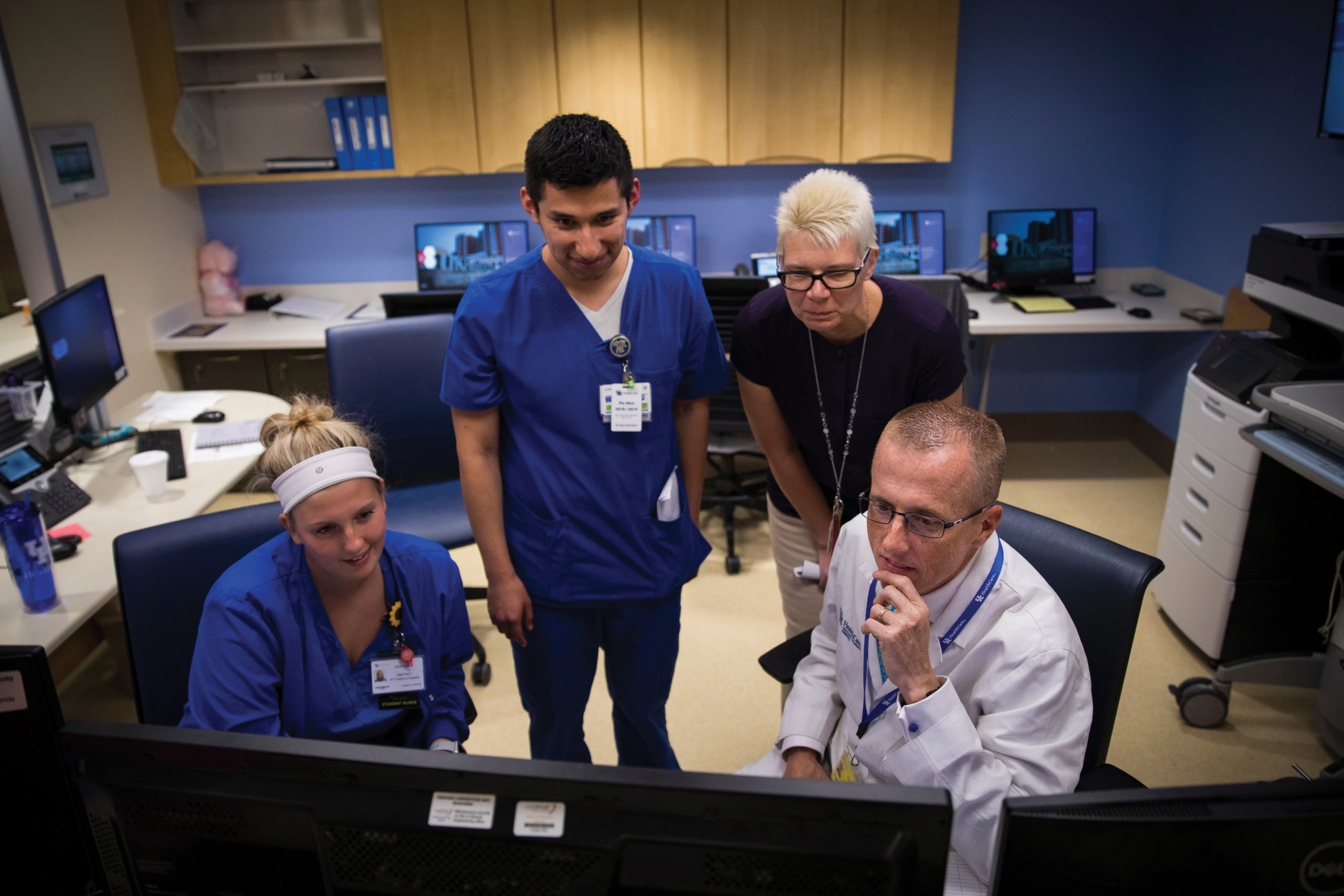

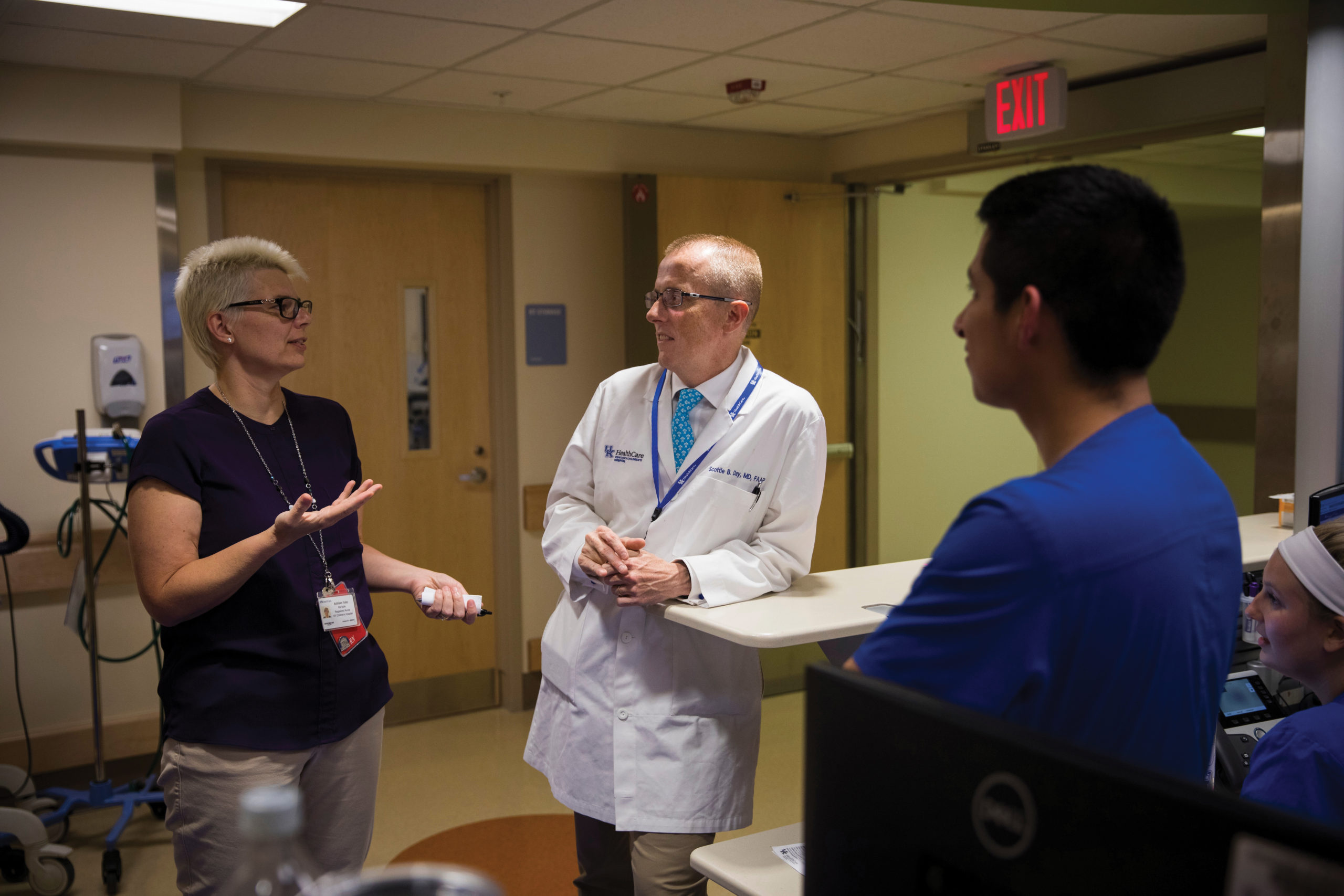

A lot of our training is based on simulation, a what-if scenario. We get everybody on the team: the front desk, the nurses’ desk, the respiratory therapist, the trainees. Everybody has a role in these scenarios. For example, what if a child comes back from the operating room and the heart rate drops: How do you problem solve? How do you work as a team? If you can constantly do these educations, then when these things come up you will be prepared, have the scenarios of what could go wrong. We spend a lot of time doing that type of training.

MG: Earlier in your career, you spent time at the respected Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Did you bring best practices from there to Kentucky Children’s Hospital?

SD: I trained in a critical-care fellowship there. I stayed an additional year through an NIH (National Institutes of Health) fellowship. From every institution I’ve been to, including my medical school, you learn and you bring back those practices. Before I went to Cincinnati, I was with Indiana University at Riley Hospital for Children as an internal medicine pediatrics resident. You take those experiences as a key component of education and you bring them to new facilities. After Cincinnati, I worked for Kaiser Permanente for a while, which was private practice and not as much academic. I learned a lot from being at that facility and how they managed care.

One of the great things about our institution is that we have individuals from children’s hospitals throughout the world. Everybody brings all those best practices together. And one size doesn’t fit all. We can measure outcomes related to surgeries or outcomes related to hospitalizations. I will tell you there are things about Kentucky that are different than Cincinnati and elsewhere such as the socioeconomics in this state. I love this population; this is the population where I grew up. But there are different needs for these children than a child in New York or in California. A lot of times we have to tailor to what works for our population

MG: You have a goal to make Kentucky Children’s Hospital the top pediatric hospital in the country. What is required to make that happen?

SD: Kentucky Children’s Hospital needs to be the best hospital not just in the state. But it’s not just about obtaining a ranking. It’s about providing care. I have four children ages 16, 14, 10 and 8. This is the hospital I want to be able to bring my child for every single service. That is the goal. As the leader of this institution, I would tell you I would bring my child here, and we’ve got to provide the care to do that.

We are part of a group, a hospital association that represents over 200 children’s hospitals across the country, and we’re constantly learning what best practices are. And they’re constantly learning from us. There are things that we are part of that allow us to make sure that our metrics are where they should be. Let’s say there are only five or six cases that we may see here of a particular illness. Well, across the country there are probably 1,000 of those. We have these consortiums that predict what this child’s outcome is going to be. When people talk about doing research or doing academics, it’s about learning from each individual patient every single time. So we have metrics to do that.

We also have a very focused group looking at what defines a best children’s hospital and where we are. What we found as we dug into it is that in many areas we are there. We showed it both in the rankings in orthopedics for U.S. News & World Report through a partnership with Shriners. And through partnership with Cincinnati with the significant rating and ranking in our joint cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery program for children. Those rankings recognize the care that we deliver. It’s not just about the rankings. It’s about the reputation, that type of mentality that all of our staff have, that this is going to be the safest place for our children.

Once we’ve gained where we are today, it’s about bringing that team together, understanding the common goal. We hear about that in athletics, in football and basketball. But we do have metrics that we want to meet. We look at this every single day. My chief medical officer for the Children’s Hospital, Dr. Ragsdale, has a daily briefing where they talk about safety, what’s going on in our hospital. Where are the places that we need to pay a little more attention? It’s a constant, daily 24/7 mentality. That’s true all the time. It’s got everybody thinking along that same way.

MG: So being the best is more of a team approach and expertise as opposed to having some physical tool in your hand?

SD: We do use all the tools. But we submit quality data for all of our infection rates. We look at access. We look at how long it takes for that child to get into see our pediatric GI specialist. Honestly, the other part of it is, let’s look at what other people are doing; maybe that doesn’t fit here, but maybe there’s some variation of it. Or we have a partnership with King’s Daughter Medical Center in Ashland, and we have a partnership now with Pikeville Medical Center. What can we do together to raise everybody? At the end of the day, it’s not about the ratings, it’s about getting these kids access when we know they’re not getting it. That’s really what it’s about. There are a lot of things we can do as a team that will get everybody further, will deliver the patient care the way they want to. And we’re proud of it.

MG: What are some of the outcome metrics that you track?

SD: One is hospital length of stay. Specific to the hospital, we really value patient experience. We always tell these families—especially in my NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) world—when you come to NICU this is a nightmare because when you had your child you would have never imagined that your child would end up in a children’s hospital. We can’t replicate home but what can we do so that they know that everybody is thinking about their child? I’ll have families say sometimes, ‘Man, you guys are so busy. You guys are just busting at the seams.’ I understand it’s hard, but at the end of the day the only child that matters in that children’s hospital to those parents is the child that sits in front of them.

The other part to is trying to help them understand that many of these kids will leave the hospital. That’s the beauty of doing pediatrics: The rate of death in any child is really, really low. One of the key factors I tell families all the time is that right now this is a nightmare and this is absorbing all of your time, but my hope would be that 10 years from now or 15 years from now this time will be one sentence, two maybe. I have practiced a long time and a lot of these families will send me a message and say, ‘You know, Dr. Day, you said this, but I never believed it.’

Unfortunately, not all the endings are great, and that is just as important to us. Catastrophic things happen to children, and I’ve had an opportunity to be at the bedside with these families. You have to realize what they’re dealing with. You have to realize the emotions, and you have to respect those emotions and you have to deal with it the best you can.

MG: What geographic footprint does Kentucky Children’s Hospital draw from? Is there a formal referral network of other hospitals that bring patients to you?

SD: There is no formal network. We serve all 120 counties in the state of Kentucky. If I pull up a list of how many patients we serve and where they’re from, there’s not a single Kentucky county that we haven’t served a patient. With our arrangement with Pikeville, we’re more involved there than ever and plan to be even more involved as we move forward. They capture a lot of patients from the West Virginia corridor. We get some patients from West Virginia, some from Ohio, and some from Tennessee. A majority of our patients historically have mostly been Central and Eastern Kentucky, but with telemedicine, with the expansion of services and their increased quality, we have more kids coming to our hospital than ever before. We also have more outpatient and ambulatory visits than ever before. A lot of the future for various specialties relies on how do we get these kids in for access? If we can get them early access to some of these things, they may never have to walk into our hospital, which is wonderful.

MG: What are the hospital’s patient numbers?

SD: With the pandemic, we did see a downturn in numbers initially because kids weren’t getting sick. Since August, we’ve seen a record number of respiratory infections, some of which have been COVID and some have been RSV. We saw more patients in August related to COVID than we saw the entire year before.

Some of the reason for those hospitalizations unfortunately has been behavioral health admissions. Actually, long before COVID-19 was even around, we were seeing a steady incline in behavioral health issues, adolescent medicine, and other related behavioral problems for children, including, horribly, suicide and eating disorders. We have continued to see that incline. With this last surge we’ve seen an even a greater incline in patients being referred to a pediatric emergency room for behavioral health or psychiatric issues. It’s not unique to Kentucky. It’s across the world, across the United States. Every day we are trying to figure out how can we partner with schools or others; how can we get on top of this. We’re going to have a pretty large strategic plan looking at how we are going to handle the crisis in mental health. A week ago, we and children’s hospitals across the country declared a national emergency related to child mental health. Some of our volume is being driven by that.

MG: It seems that an awakening is happening across society about the value of providing more and better mental health care. Is one reason for seeing more cases because we are removing the stigma? People are willing to talk about it and seek care?

SD: Recognition is a part of it. I also think we have children now going to a more severe means—these are suicide attempts and as young as 10 years old. As a father, it’s probably one of the most frightening things ever because we can’t predict necessarily who’s kid it’s gonna be. This is across all socioeconomics. There are some predictable factors related to economics absolutely, but in general it doesn’t discriminate. Talking about it has been important and there’s an increased recognition, but it’s beyond just recognition.

As a children’s hospital, people ask, ‘What’s the future of Kentucky?’ How are you going to predict what it’s going to look like 10 or 15 years from now? The generation now in our children’s hospitals and in our schools, the generation we’re trying to get more mental health to, they will be the generation that will determine the future of this state. That’s why this is so key. How do we make this happen? We have key partnerships through our adolescent medicine group in schools to try to help with recognition, to try to train, but we’ve got to do better. I’m not talking just finances; I’m talking investing to put in the energy. These are the people who are going to be in their 20s and 30s and making decisions for us. It’s the beauty of the job that we get to do this. This is what’s key to being a children’s hospital.

MG: What are the most common reasons in pediatric medicine that require hospital care?

SD: The largest population most of the time is in neonatal ICU. We’ve seen an increase in the past year and some of that in Kentucky is related to neonatal abstinence and the opioid problem, which did not go away. The other is that mom sick with COVID; a lot of those children had to be taken prematurely, more prematurely. Moms got really sick through this pandemic, the unvaccinated ones; we had a lot of prematurity from that. Prematurity is a big population in NICUs.

The positive of it is that we are now resuscitating babies at 23 weeks, meaning those are viable children at 400-something grams, smaller than my palm here. That drives the population of kids who survive and some have quite great outcomes. Do some of them have complications? Absolutely, but they survive.

The other populations that you get with the babies are some of the viral illnesses, whether it be respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), COVID and kids born with congenital heart conditions, diabetes. There are a lot of chronic things that aren’t that common that can happen that hospitalize them.

The other populations are trauma and child abuse. Unfortunately, Kentucky leads the nation in child abuse, which is not something we’re proud of. Part of it is that we are recognizing it better, but we’ve been a leader in that area for a while. We work with Kosair Charities and other organizations to focus in on that. We’ve recruited and now have three faculty members led by Dr. Christina Howard who look at child abuse and work with agencies across the state to better address that so those kids don’t end up in the hospital.

MG: Are there unique characteristics to Kentucky that push certain health conditions higher or conversely, are we better in some areas?

SD: Some of the challenges we face in Kentucky and specifically in Appalachia and some of central Kentucky are resources. Some children have chronic health conditions; finding resources in certain other parts of the state is challenging. We’ve had families have to move closer to Lexington. Our partnerships with various agencies—whether it be with Appalachian Regional Hospitals or Pikeville Medical Center or Baptist Health, CHI Saint Joseph Health or Lifepoint or King’s Daughters Health System—help provide resources to keep families in those communities. The economics of the opioid challenge is that a lot of those are parents with children who are displaced. With the pandemic, people have lost their primary caregiver; that changes the dynamics in the family. We are working through Dr. James Van Buren, medical director of the Department of Juvenile Justice, to figure out how to help them not just in medical health but with the psychiatry department. Imagine a child has been in the juvenile justice system at such a young age; what’s going to be the predictive factor in that child? There’s a good chance that child is going to end up back in prison, so we’re trying to figure out how can we invest energy and time into these children who have had very adverse child experiences—almost 100%, something catastrophic, whether it be abuse or neglect. Neglect is a big one here in the state.

Regarding statistics: As a guy who grew up in Leslie County, the son of a coal miner—in my office you see my father’s coal miner’s hat—statistically no one would predict I would be sitting here today. It’s not because we’re not smart enough; it’s just sometimes the statistics are the statistics. To me, investing in one individual changes generations to come. It may only be one out of 10 kids who ends up doing something, but that changes a generation to generation to generation. So investment in that child will change many generations to come. I tell people: That one child will change more than just that one child.

MG: What are the key revenue sectors and trends in pediatric hospital care?

SD: In neonatal ICU, a majority of our population is Medicaid; 70% of our volume is Medicaid. But obviously, we take care of all insurers. As far as the financial trends of most children’s hospitals across the country, NICU and the ICUs are the big ones. However, in general a children’s hospital is very dependent upon having a foundation or an endowment or a philanthropic entity to help them cover all the missions. This is throughout the country, which is why you hear about all these different hospitals that carry names of persons or organizations in that community who have come forward and said this is a valuable resource, we want this children’s hospital to survive. The revenue trends that make us viable and provide long-term sustainability require those partnerships.

We’re Kentucky Children’s Hospital at UK Healthcare, but we have agencies that spend a lot of energy and time helping us carry on those missions that aren’t covered through the typical payor mix. For example, DanceBlue has done a ton to help provide Child Life (a specialized service providing play opportunities for pediatric patients) and other services. The Makenna David Foundation also. A lot of it is driven by people who had an experience, like Jarrett Mynear or Makenna David or Coaches for the Kids, organizations that said, ‘These people are real and this is where we want to make a difference in Kentucky.’ We are dependent upon having a great and hopefully growing philanthropic base to cover all those missions.

MG: There is a shortage of doctors and nurses, especially in rural areas. What is the staffing situation for pediatric?

SD: It’s a challenge. It’s not unique to us. It’s challenging to get individuals to go into pediatric medicine and its specialties. We’ve been very fortunate to be able to get a lot of phenomenal specialists here, but it’s not easy. Not a lot of people in the country choose to do pediatric medicine or be pediatric specialists. Pediatricians are the lowest paid providers in the country. Not that people go into medicine for that, but it involves so much. For pediatric providers, you’re involved in that child for many years to come. And when you see a pediatric patient you have mom, dad hopefully, you have grandma, grandpa. You become a part of their family. I’m an ICU doctor so they only see me when their kids have been ill. That’s true of so many of our providers. The stress and burnout that creates is significant for some specialists, which is one of the reasons you’re hesitant to go into that. There’s demand in nursing across the country. In children’s care we need more nurses. And it’s not just nursing, it’s sonographers for ultrasounds of the heart, electrocardiogram techs. It’s the whole list.

MG: Is there more childhood diabetes now than there used to be and if so, why?

SD: You are correct: We’ve seen an increase of diabetes. In diabetes related to older children or adolescents, absolutely there is more. We know some of that is unhealthy choices. Some of it’s not clearly understood. Unfortunately, obesity is an issue for the state of Kentucky so a lot of that increase is related to that, especially in the new diagnoses of adolescents. We have seen an increase in diagnoses in (Type 1 among younger kids). It is probably too early to tell why. Our pediatric endocrinologist would be able to give you more specifics on the increase in numbers.

MG: For many health conditions, early detection is a crucial element to successful outcomes. How do we do at early detection for childhood medical conditions?

SD: We have a newborn screening program and work with the state to provide that service so every child has a screen for certain conditions and we make sure they follow up. We work with the primary care pediatricians throughout the state. We do a pretty good job of newborn screening. One thing we and the general pediatrics pediatricians are working harder on is getting people back in for well-child checks. During the pandemic we saw a dramatic decrease in people bringing their children in. Everybody was scared, appropriately. There are well-child checks at two weeks, checks at a couple of months. They’re not just for vaccines. Are they growing? Are they developing? Are they rolling over? Are they speaking? We need to focus on that. It became especially challenging for school-age children missing their well-child checks. And they weren’t in school, so how do we detect a lot of things?

The second thing with early detection is identifying that someone has a mental health disorder or has increased anxiety and getting on top of it. Most of the children who have tried or committed suicide had been seen by a health care professional within the last week or so. For child abuse even more so. How do you create an environment not just to be detective but to make it OK to say that I’m worried? Those are the top detections we want to make, especially for the babies coming for the well-child checks.

MG: What are the benefits to all of us in providing better childhood health care?

SD: The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s annual Kids Count on state trends in child well-being has a look at Kentucky overall and a lot of what happens in our future is the health of now. There have been some exciting announcements for the economics of this state in the past couple of weeks and this will continue. But how do we make sure we continue to build a workforce that can work in these positions? In this Kids Count we have 22% of Kentucky children living in poverty, and that was as of 2019—so this isn’t even post-pandemic. We have over 30% whose parents lacked employment.

Another thing we focus on is prematurity and low-birth-weight babies, so we have to look at the moms. There’s phenomenal research that outcomes start when the baby is in utero, with the health of the mom. I’m not just talking about neonatal care abstinence. We need to talk about the health of the mom: Do they have nutrition? We don’t want to be smoking. Low birth weight babies are a huge issue. For the state, the March of Dimes gives us a grade of D on an A-to-F scale in prematurity. We work with them and other organizations to look at the communities and the family and resources. There are many things we can do.

How do you fix statistics? Lots of times people look way downstream: If you’re trying to address the Mississippi, don’t go look at the Atlantic Ocean; you might look at the Gulf of Mexico to see what’s there, but you need to start way upstream. We need to start all the way up at the top, and childhood health care is that “upstream” that affects the future. We won’t see it for a long time. It’s like a river whose impact you’re not going to see until it gets in the ocean, but I can tell you if you make those little investments, eventually it makes a big difference.

MG: What are the top health outcome indicators for children generally and in Kentucky specifically?

SD: The top predictor of health from a lot of foundations is your rate of prematurity. One of the other predictors is children and teens who are overweight or obese. About 37% of Kentucky children were overweight or obese. Based on teen data, that is probably close to 50%. This gives you an overall prediction how those children are going to do. Economics plays a role in it as well and teen births is a another one. Obviously, the hospital plays a role both when admitting a kid and on an outpatient ambulatory screening basis. It’s multifactorial. A lot of kids who might never get admitted are screened and we do something, whether it be an eating disorder, obesity, mental health, prematurity. Those things really predict long-term outcomes.

MG: Especially during the pandemic, telehealth took great strides forward in usage and the impact that it’s having. Is this happening in children’s care as well?

SD: We already had a telehealth platform prior to March 2020. We were fortunate as an organization to be ready to flip the switch quickly to do more telehealth. It has revolutionized our care in Kentucky for children. For example, adolescent medicine: Teens may not want to come to clinic, but they may be perfectly fine doing telemedicine. We have telemedicine in every single practice now. It is part of our daily workflow. For some families, especially now with gas prices, it could be very expensive for transportation to get a child here. For some follow-up appointments that we do, telemedicine is beautiful for that. It saves them the travel and allows some families to “come to” the appointment. Finding gas money can be quite taxing, or more importantly, if they live in the eastern part of the state it can be 2½ hours here, 2½ hours back, or 3 hours, 4 hours. They’ve lost the whole day of work. The economics of that are so important for people to understand.

MG: Do you have any closing comment?

SD: We have the opportunity as a children’s hospital to think about us not just as a hospital but as a health care organization truly invested in the future of Kentucky. We may not see the results of what we do today until 10 years or 15 years down the road. People say, ‘How are we going to change Kentucky? How are we going to make sure there’s a workforce 10 years or 20 years from now?’ People need to think about that.

This is going to sound corny, but we need to think about how to love people again. People are still dying every day. I’m not saying it should create anxiety or depression, but we should say, ‘OK we have to do something.’ One of my favorite quotes is by Mark Twain: “The two most important days in your life are the day you were born and the day you figure out why.” I would never imagine, growing up in Eastern Kentucky, I would ever be sitting here today talking with you as the leader of a children’s hospital. Anything’s possible. I spend a lot of time mentoring other people, people from all walks of life, partnering with other people, because I can tell you we’re not going to go very far if it’s just me; I might go fast, but we’re not going to go far. To reach what we need to be and to have been able to become at this children’s hospital has taken such a team effort. I’m very honored to have a chance to tell you about who we are, what we are, and what we want to do.

Click here for more Kentucky business news.