Two venerable Kentucky industries – hemp and horses – are thriving, which is good news for the banks and other lenders serving those spaces, and for the commonwealth’s economy.

The hemp industry is expanding thanks to its recent legalization, building on gains made during a five-year pilot program. Kentucky is considered to be the leader in industrial hemp growth and production. For horses, a good economy and some favorable tax treatment have helped the industry regain much of the steam it lost during the Great Recession.

Decades ago, hemp was a staple of Kentucky agriculture, but it shared an unfortunate connection with marijuana, the intoxicating strain of the genus Cannabis. Hemp also contains tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the component that gives marijuana its psychoactive trait, but at levels that are a fraction of those found in marijuana. That association, though, put hemp and marijuana together on the Controlled Substances Act’s list of Schedule I drugs and substances, which includes heroin, psilocybin and peyote.

Hemp has long had its advocates – the strength of its fiber made its use popular in clothing and other textiles prior to being listed as a banned substance. But it wasn’t until 2014 – when the Farm Bill passed by Congress allowed states to begin hemp research pilot projects to study methods of cultivating, processing and marketing industrial hemp – that the crop gained a solid foothold.

In 2017, the Kentucky legislature passed Senate Bill 218, which among other things clarified the Kentucky Department of Agriculture’s role in hemp farming and production and brought the state’s pilot program into better alignment with the 2014 Farm Bill.

Then in 2018, Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell got language legalizing hemp growth and production into the 2018 Farm Bill. Under the bill, hemp with THC content of 0.3% or less became legal to farm, sell and process. This opened the door to hemp fiber’s use in clothing, textiles, paper and other industrial uses, and to the use of its derivatives in nutraceutical and pharmaceutical products, including cannabidiol (CBD) oil.

Kentucky has been readying itself to take the lead in hemp cultivation and production since the pilot program was launched. As a result, since 2014 the commonwealth has seen a rapid expansion of both hemp acres and production facilities.

According to the KDA, during the first year growing hemp under the pilot program, 33 acres were planted. That increased to 922 acres in 2015; 2,350 acres in 2016; 3,200 acres in 2017; and 6,700 acres in 2018. The KDA actually approved up to 16,100 acres for hemp planting last year. This year, that figure grew to 57,000 acres approved for planting, although the KDA does not yet know how many acres have actually been planted.

- IT’S FREE | Sign up for The Lane Report email business newsletter. Receive breaking Kentucky business news and updates daily. Click here to sign up

Kentucky Agriculture Commissioner Ryan Quarles said the acreage “translates into real dollars and cents for the commonwealth.” Hemp processors reported to state authorities $57.75 million in gross product sales in 2018, compared with $16.7 million in 2017. Those processors, in turn, paid hemp farmers $17.75 million for their crops in 2018, up from $7.5 million the year before.

Kentucky lenders are noticing the uptick in activity, although they say further clarification by financial regulators that it is permissible to work with hemp growers and producers; the availability of crop insurance for farmers; and another cycle of hemp growth, production and processing could really take the lid off industry growth.

Jonathan Noe, vice president and chief lending officer at Central Kentucky Ag Credit in Lexington, said the cooperative lending institution recently adopted a policy to finance hemp production and processing. But AgCredit is proceeding “with caution,” Noe said, because it’s still a new industry and the businesses involved in it do not yet have long track records.

“Anytime we have an upstart business, even if it’s in an established industry, we proceed with caution,” Noe said. “But we’re cautiously optimistic. We see real potential out there. We see a lot of invested dollars here in Kentucky because, to be quite honest, Kentucky is in the lead when it comes to hemp production.”

One important ingredient that’s missing is written regulations that allow for farmers to have crop insurance through the Federal Crop Insurance Corp. The lack of insurance limits the amount of money that AgCredit can lend to hemp farmers because it has to ask for more tangible collateral, such as real estate and equipment to secure the loans, Noe said. With other kinds of farming such as corn, soybeans or tobacco, AgCredit can take a lien on the value of the crop, backed by crop insurance.

Noe said it’s a simple matter of regulators needing time to write those crop insurance rules. “It’s just not in place yet. The Farm Bill was signed in late 2018, so we’re only a few months into this, and I think it’s just a matter of we haven’t had the time at the federal level to get all the regulations written. It’s just a matter of time. We feel like [in] 2020, things are going to open up quite a bit.”

Oddly, though, legal certainty for hemp has resulted in a near-term contraction of financial services available to hemp growers and producers. After President Donald Trump signed the Farm Bill into law last December, some credit card processors stopped offering their services to hemp product sellers.

Part of the reason why stems from uncertainty among banks and financial institutions with respect to dealing with cannabis-related businesses. Hemp’s long association with marijuana, and marijuana’s recent dual status as legal in some states but still technically illegal at the federal level, combined with very different treatments of that dual status by the justice departments of the Obama and Trump administrations means banks have tended to treat hemp financial transactions similar to how they would treat other cannabis transactions. Typically that means filing what are known as suspicious activity reports (SAR) whenever they conduct business related to cannabis. This includes credit or debit card transactions.

As it turns out, that has had a chilling effect on financial services companies’ willingness to deal with both marijuana- and hemp-related businesses.

But just as McConnell worked to push the hemp provision through in the Farm Bill, Kentucky Sixth District Rep. Andy Barr, a Republican, has been pushing for industrial hemp farmers’ and producers’ access to financial services. At a May meeting of the House Committee on Financial Services, Barr asked FDIC chair Jelena McWilliams, Comptroller of the Currency Joseph M. Otting and Vice Chair for Supervision at the Federal Reserve Randal K. Quarles to issue a statement together clarifying that industrial hemp and marijuana are not the same and that industrial hemp businesses should have access to financial services.

McWilliams acknowledged that there is uncertainty in the space and said that the FDIC is training its examiners to ensure they understand what’s legal where and that they do not put “undue pressure” on hemp businesses. She said the FDIC tells banks to follow guidance issued in February 2014 by the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, which essentially tells financial institutions to decide on their own, on a case-by-case basis, whether to provide services to marijuana-related businesses, taking into account customer due diligence and an evaluation of the risks. It recommends filing a SAR whenever the financial institution suspects a transaction involves illegal funds, is meant to bypass regulations or lacks a business or lawful purpose. The guidance doesn’t mention hemp specifically.

That’s not good enough for Barr, who said he sees himself as an advocate for industrial hemp, for Kentucky banks and credit unions, and for Kentucky farmers. In the 2018 congress, Barr introduced the Industrial Hemp Banking Act, which would have established a safe harbor for depository institutions providing credit or other banking services to participants in the hemp pilot program. That bill died in committee. In the current congress, Barr is working with U.S. Rep. Ed Perlmutter (D-Colo.), who authored a bill called the Secure and Fair Enforcement (SAFE) Banking Act. That bill would provide legal certainty for financial institutions dealing with legitimate marijuana-related businesses in states that have legalized marijuana use.

Barr said Perlmutter has agreed to sponsor two amendments that Barr wants added to the bill when it reaches the House floor that would address the issues the hemp industry is having accessing card processing and banking services.

“The way we’ve drafted our amendment, it would not require any additional SAR reporting for a legal hemp business because it’s legal under both state law and federal law now,” Barr said.

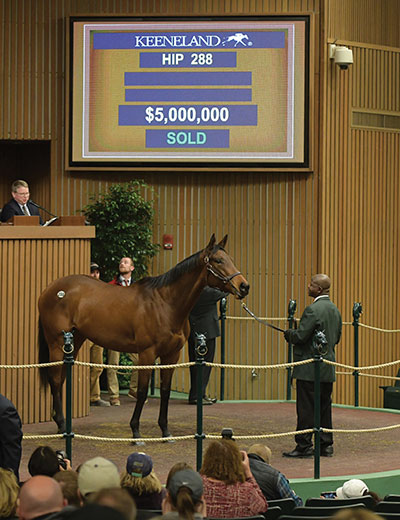

While hemp lending is poised to take off, lending in the equine industry is well on its way to recovering from its lows during and immediately after the financial crisis a decade ago. A couple of Triple Crown winners, a successful World Equestrian Games in 2010, a growing economy, and more favorable tax treatment of business expenses, including buying horses, are helping fuel growth in equine lending.

Russell Gray, vice president of credit at AgCredit, said both the Thoroughbred and sport horse lending businesses are strong, but he gives the edge to the sport horse side of things.

In sport horses, AgCredit makes loans primarily for real estate purchases and capital improvements on farms. “We see people who come in and pay cash for the farm and then follow up later with us to build the indoor arena,” Gray said. “Those things can be $250,000 to a half-million dollars, depending on the size and how extravagant they want it to be. If you buy raw land, you’ve got to put the water lines in, you’ve got to build those miles of four-plank fencing and paint them, you’ve got to put blacktop roads in, build the barns, build a home, etc.”

On the Thoroughbred side, Gray said AgCredit loans money for purchasing land and property improvements. He said the industry tends to run in seven- to 10-year cycles, up and down with the inventory of yearlings. He said the Thoroughbred industry has tended to be supported by nonfarm income: financially well-off people who’ve made their money elsewhere decide they want to own a horse farm or be involved with horses either due to a new interest or because of family connections.

“Many, many times the loans I work with have very strong nonfarm income to support their farm ownership,” Gray said. “You can’t be a pauper and own $20,000-an-acre land and borrow money on it.”

Thanks to the long global economic expansion, times have been good for Thoroughbred farms and, by extension, lending.

Furthermore, one part of the tax law changes in 2017, Section 179, allows taxpayers to more easily deduct the entire purchase price of a property, including a horse, under certain conditions.

Gray said he’s also seeing more international buyers acquiring farmland in Kentucky, and not just from Ireland or the Middle East. People from several South American countries have been making purchases here as well.

“These people are financially well off,” he said. “They’ve been in the business for some time and just finally made the decision to buy farm real estate here in Central Kentucky.”

Chris Clair is a correspondent for The Lane Report. He can be reached at [email protected].

Add Comment