Editor’s note: This commentary by Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions of San Diego is made available by American Financial Consultants of Columbia, Ky.

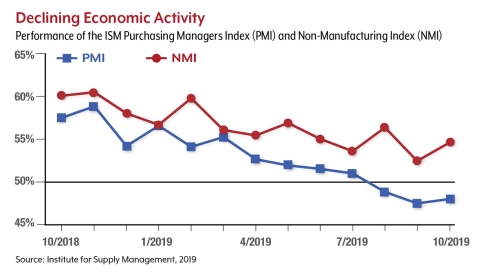

In September 2019, the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Purchasing Managers Index (PMI), which measures a wide variety of manufacturing data, fell to 47.8%, the lowest level since June 2009.[1]

A reading below 50% generally means that manufacturing activity is contracting. The August reading of 49.1% had signaled the beginning of a contraction, and the drop in September suggested that the contraction was not only continuing but accelerating. The index rose slightly to 48.3% in October, but this indicated the third consecutive month of contraction.[2] Nearly two-thirds of economists in a Wall Street Journal poll conducted in early October said the manufacturing sector was already in recession, defined as two or more quarters of negative growth.[3]

Leading indicator

The PMI — which tracks changes in production, new orders, employment, supplier deliveries, and inventories — is considered a leading economic indicator that may predict the future direction of the broader economy. Manufacturing contractions have often preceded economic recessions, but the structure of the U.S. economy has changed in recent decades, with services carrying much greater weight than manufacturing. The last time the manufacturing sector contracted, during the “industrial recession” in 2015 and 2016, the services sector helped to maintain continued growth in the broader economy.[4]

That may occur this time as well, but there are mixed signals from the services sector. In September, the ISM Non-Manufacturing Index (NMI) dropped suddenly to its lowest point in three years: 52.6%. The index bounced back in October to 54.7%, marking the 117th consecutive month of service sector expansion. Even so, these recent readings were well below the 12-month high of 60.4% in November 2018.[5]

Global weakness and trade tensions

The slump in U.S. manufacturing is being driven by a variety of factors, including a weakening global economy, the strong dollar, and escalating tariffs on U.S. and imported goods.

In October 2019, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) downgraded its forecast for 2019 global growth to 3.0%, the lowest level since 2008-09. The IMF pointed to trade tensions and a slowdown in global manufacturing as two of the primary reasons for the weakening outlook.6 Put simply, a weaker world economy shrinks the global market for U.S. manufacturers.

The strong dollar, which makes U.S. goods more expensive overseas, reflects the strength of the U.S. financial system in relation to the rest of the world and is unlikely to change in the near future.7 Tariffs, however, are a more volatile and immediate issue.

Originally intended to protect U.S. manufacturers, tariffs have been effective for some industries. But the overall impact so far has been negative due to rising costs for raw materials and retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports. For example, tariffs on foreign steel, which were first levied in March 2018, enabled U.S. steel manufacturers to set higher prices. But higher prices increased costs for other U.S. manufacturers that use steel in their products.8 Retaliatory tariffs by Canada and Mexico contributed to a $650 million drop in U.S. steel exports in 2018 and a $1 billion increase in the steel trade deficit.9 (In May 2019, the United States removed steel tariffs on Canada and Mexico, which dropped retaliatory tariffs in return.)10

U.S. manufacturers in every industry may pay higher prices for imported materials used to produce their products. An average of 22% of “intermediate inputs” (raw materials, semi-finished products, etc., used in the manufacturing process) come from abroad.11Tariffs paid by U.S. manufacturers on these inputs must be absorbed — cutting into profits — and/or passed on to the consumer, which may reduce consumer demand.

The uncertainty factor

Along with specific effects of the tariffs, manufacturers and other global businesses have been hamstrung by trade policy uncertainty, which makes it difficult to adapt to changing conditions and commit to investment. A recent Federal Reserve study estimated that trade policy uncertainty will lead to a cumulative 1% reduction in global economic output through 2020.12

On October 11, 2019, President Trump announced that he would delay further tariff hikes on China — including an increased tariff on intermediate goods scheduled for October 15 — while the two sides attempt to negotiate a limited deal. Although a deal would be welcomed by most interested parties, past potential deals have collapsed, and it’s uncertain how any agreement might affect the $400 billion in tariffs on Chinese goods already in place, or the tariffs on goods from other countries.13

Will the slowdown spread?

Manufacturing accounts for only 11% of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) and 8.5% of non-farm employment, a big change from 50 years ago when it accounted for about 25% of both categories.14-15 However, the manufacturing sector’s economic influence extends beyond the production of goods to the transportation, warehousing, and retail networks that move products from the factory to U.S. consumers. The final output of U.S.-made goods accounts for about 30% of GDP.16

Even so, a continued slowdown in manufacturing is unlikely to throw the U.S. economy into recession as long as unemployment remains low and consumer spending remains high. The key to both of these may depend on the continued strength of the services sector, which employs the vast majority of U.S. workers. It remains to be seen whether the service economy will stay strong in the face of the global headwinds that are holding back manufacturing.

Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions does not provide investment, tax, legal, or retirement advice or recommendations. These materials are provided for general information and educational purposes based upon publicly available information from sources believed to be reliable

Nice Post! thanks for the share in manufacturing.