Kentucky’s record success at landing billions in private business projects is the result of years of public effort to get upstream in an ever-faster industrial site-selection process.

Kentucky’s record success at landing billions in private business projects is the result of years of public effort to get upstream in an ever-faster industrial site-selection process.

Speed-to-market is considered the decisive factor in where companies put projects today. Time is money and only shovel-ready property merits serious consideration.

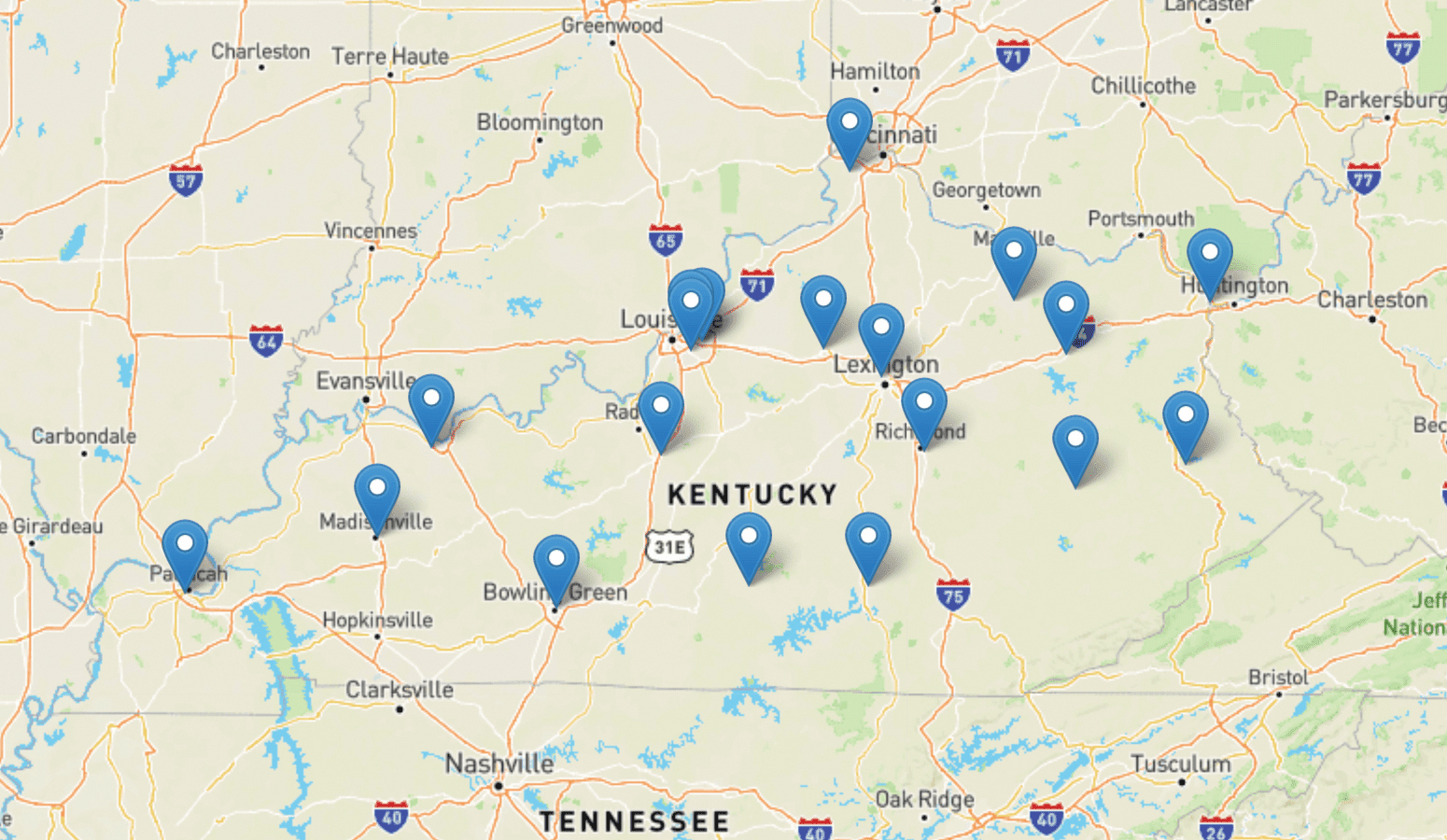

Kentucky communities are doing a better job of providing such sites. This is due to strategic efforts begun decades ago and a recent pilot program to strategically fund finishing out properties. The program’s effectiveness led the state to put $200 million behind it this year.

“You have to compete more often to win more often,” said Ron Bunch, CEO of the Bowling Green Area Chamber of Commerce, whose successful innovations are bringing huge projects, good jobs and population growth. “Now is the time for all of us to step up and be more competitive.”

Economic developers think state site-preparation strategy sets the pace nationally. And Kentucky is not only more competitive than ever, it’s angling for an even better advantage.

“Kentucky is doing very well in this space, there’s no doubt about it—not just on the mega projects, but the day-to-day projects,” said Lee Crume, CEO of Northern Kentucky Tri-ED, which pursues economic growth for Boone, Campbell and Kenton counties.

Five to six years ago, Kentucky’s utilities partnered to pay a consultant to conduct a survey and make recommendations to improve economic development outcomes. The main finding was that the commonwealth was not offering site selectors shovel-ready locations. In 2018, the state began a pilot program to award grants for finish work on local sites, with communities required to match that state money to have some skin in the game.

The Kentucky Association for Economic Development (KAED), the professional organization for the state’s local economic development offices, ran the pilot with help from Site Selection Group, a Dallas, Texas, consultant deeply experienced in guiding private company location decisions. Site Selection Group graded grant applications made by Kentucky communities and ranked them by likely impact.

The commonwealth’s $9 million in Product Development Initiative (PDI) grants netted $600 million in private investment.

“I expect we will see over a billion dollars of return on this ($200 million in state funding). I think it will be significantly north of that,” Gov. Andy Beshear said. “These are days where just one project could potentially do that.”

Demand for sites is at a peak

With insight that the investment paid handsomely, the General Assembly this year put $200 million toward helping the state land more of the action that a global business evolution is generating.

Consumer demand for environmentally responsible business operations is driving a once-in-a-lifetime shift to electric-powered vehicles. The ongoing pandemic exposed supply chain vulnerabilities that businesses are addressing by relocating vital operations back to the United States. Workforce shortages are compelling industry to shift to operations that use technology to accomplish processes that will meet demand and achieve growth.

These trends are keeping economic developers in Kentucky and elsewhere busy supplying the sites that allow industry to modernize.

In response to site demand, Bowling Green and Warren County issued $46.5 million in bonds 18 months ago to invest further in the successful Kentucky Transpark, a 1,000-plus-acre intermodal site along I-65 with CSX rail service. Transpark was created and developed two decades ago with previous community-backed bond sales.

Home now to 19 private companies and three education facilities, Transpark in May landed a transformational megaproject, a $2 billion electric-vehicle battery gigafactory that will employ 2,000. Envision AECS, the Japanese subsidiary of China’s Envision Group, will build its EV battery plant on 500 acres.

The PDI pilot, which began while Bunch was chair of KAED, provided money that helped land three recent projects, including Envision, he said.

Bowling Green’s megaproject would be the largest in Kentucky history except that eight months earlier Ford Motor Co. and SK Innovation of South Korea chose a site 50 miles north for an even bigger EV gigafactory, BlueOvalSK Battery Park. Twin battery gigafactories are being built on 1,500 acres near I-65 and will employ 5,000 starting in 2025.

The two EV megaprojects give Kentucky the leading role in a just-emerging industrial sector that itself will require new supply chains and bring additional large private investments and job creation to the region.

“What we’re seeing from our major businesses is they now not only want their supply chains in America, they want it as close as they can to their major facilities,” Beshear said. “They want redundancy within their supply chain so that if one of their suppliers is impacted, or where they get their raw materials, that they have another supplier they can turn to. I think you are going to see more operation among clusters of industries not to have the same supply chain but to have redundancy in each other’s supply chain.”

“We call that a ‘fast and furious’ ”

It is a busy time for those connected to the industrial project pipeline. The number and size of projects seeking sites is at a high.

Crume said that when he conducted a “pipeline analysis” several years ago for his previous employer, Jobs Ohio, projects of $250 million and up were reported separately so as not to skew the general insights.

“Today that is a very routine project,” he said.

Last year, Tri-ED worked with nine prospects whose capital investment topped $300 million; four of the projects were more than $500 million.

“They either shopped us last year or could still be in our pipeline,” Crume said in late May. “We are absolutely seeing this effect of mega-projects in our pipeline and in the work we do.”

A PDI grant for natural-gas infrastructure was instrumental in Pratt Paper’s decision to choose Henderson for a $300 million project that has since grown to $500 million and will bring 350 permanent jobs.

Henderson Economic Development Executive Director Missy Vanderpool says her organization has had a good experience with PDI.

“It’s a great program, because it’s so important for your sites to be ready,” Vanderpool said.

With the pandemic creating a spike in e-commerce and increased demand for Pratt’s boxes—“their boxes are lighter weight and more economical,” she said—speed-to-market is a priority for the company.

“We call that a ‘fast and furious,’ ” Vanderpool said of the Pratt interaction. “From first visit to announcement was three months. The ability to meet their timeline was critical.”

Vanderpool said Henderson Economic Development continues to meet with Pratt officials at least every other week to ensure that the community is meeting the timeline and infrastructure goals and to get in front of any potential issues. HED also communicates at least weekly with the project manager for the Pratt project in the state Cabinet for Economic Development.

“Good product” requires many steps

Rick Games, president/chief operating officer of the Elizabethtown/Hardin County Industrial Foundation, said he “would tend to agree” that Kentucky’s site-development game is tops in the nation. There is no definitive tool to measure this, but there have been lots of “win” announcements around the commonwealth, and PDI is improving outcomes, according to Games, who has been with E/HCIF for 21 years.

Hardin County landed the BlueOvalSK project last September without PDI money but was one of the first to successfully apply for a grant two years ago for another property. The PDI grant paid for improvements to a site that “several” prospects are looking at now.

“It used to be that you could market a cornfield,” Games said. “Now you’ve got to have a (prepared property) if you’re going to get people interested. You’ve got to have a product, and you’ve got to have a good product.”

Few communities in Kentucky and elsewhere had economic development sites that were prepped and ready in the past.

“Now everyone has them,” he said.

The 1,500-acre Glendale site where work on the BlueOvalSK Park is underway has been in development more than 20 years, having been acquired around the time Games went to work for the industrial foundation. It adjoins I-65 and has CSX rail tracks, but there are many more factors involved in making a site attractive in today’s speed-to-market environment, he explained.

To become “product,” what might once have been a cornfield must have soil borings, undergo archaeological investigation, be assessed for wetlands, be evaluated for possible historical significance, and be reviewed for environmental issues such as contamination and the presence of sensitive flora and fauna. The various reports by certified experts on their findings and any remediation must be available for review and typically no more than five years old, Games said. Good products need a large and leveled building pad, appropriate zoning, water lines, sewer lines, electric service, broadband internet, drainage, roadway access, parking and perhaps rail lines or a river port.

The economic development culture has greatly changed since the state and Hardin County acquired the Glendale land.

“Twenty years ago, we were using a fax machine,” Games said. “Someone would send you a fax with a question, and they’d want a reply in two or three weeks. Now it’s two or three minutes.”

Prospect companies that have decided market conditions warrant expansion or a new location have stronger financial controls today.

“They are spending money,” he said. “The quicker they can get to market, the quicker the bleeding stops.”

Members of local economic development operations around the state have expressed their appreciation to the General Assembly and the Beshear administration for having the understanding and insight to develop House Bill 745 to codify the PDI grant program into Kentucky statutes this year, create a separate funding process for megasites and put $200 million in the new biennium budget.

The first $100 million is for the Product Development Initiative matching grant process in 2022-24. Communities must make detailed application for specific improvements to publicly owned sites.

The second $100 million is to give state and local officials megaproject rapid response dealmaking options.

State government’s action is a reflection of the level of activity in project pipelines.

“We’re going to see huge numbers of suppliers for electric-vehicle battery production,” Beshear said. “With Ford and Envision, we are by gigawatt hours the electric-vehicle production capital of the United States of America. You will see more people moving

towards where some their most important suppliers are if they are looking at establishing a new operation.”

Ashland Alliance has hosted more prospect site visits in the past six months than it did in the previous two years, said President/CEO Tim Gibbs.

“A lot of companies are looking for facilities in the U.S. and if you’re looking for a site in the U.S., we are centralized with a low cost of operations,” Gibbs said. “Everyone in the state of Kentucky is going to have real opportunity in this (present) economy and the economy that is going to develop from the $8 billion in projects just announced.”

Some of the prospects Ashland Alliance has interacted with, he said, are related to the vehicle-battery production coming along the I-65 corridor 180 miles to the west. The supply chain infrastructure to support the two announced battery manufacturing projects does not exist and will have to be created in the next three to four years.

“In many, many ways our economy is resetting,” Gibbs said. Companies’ confidence in relying on just-in-time efficiency is breaking down. “They need presence in or near their market. It doesn’t matter if it cost less (to make in a foreign country) if you can’t get it to market.”

Shipping containers and ships have become much more expensive or are not available, he said. A lot of companies are looking for facilities in the U.S., and Kentucky is both centralized and has a low cost of operations.

Economic development leaders point out that no other state has three major air freight hubs: UPS Worldport in Muhammed Ali Louisville International Airport plus the Amazon Air Hub and DHL Express Super Hub at Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport.

“We can put anything you make anywhere in the world overnight,” KAED Chairman Bob Helton said.

“Since the pandemic,” Bunch said, “being ready to move quickly is at a premium today.”

After winning a $127 million Ball Corp. project to make aluminum beverage containers last year, it was only six months from groundbreaking until the company began operations in a 500,000-s.f. facility at the Kentucky Transpark in Bowling Green.

Using its own revenue, Bowling Green is always developing potential sites, Bunch said, but PDI allows it to do more things at one time.

The PDI program “is very structured financially to ensure money goes to projects that will be successful,” said Helton. He and former KAED CEO/President Matt Tackett give credit to Site Selection Group for its advice in how to craft the grant application process and especially for its grading and recommendation of applicants.

Since the pilot began, the state’s ability to offer shovel-ready property has risen from near the bottom nationally to near the top.

HB 745 garnered unanimous support at each step of the legislative process and Beshear signed it into law at the KAED Spring Conference in Owensboro in late April.

“That really sets Kentucky apart in the nation for the money available for economic development,” Helton said. “It speaks to the perceived importance of economic development in Kentucky.”

“No other state is doing what Kentucky just did and that is to be celebrated. It will be incredibly and potentially transformative for the commonwealth,” Tackett said.

PDI calls for the Cabinet for Economic Development to partner with KAED to run the program. Each county in the state may apply for a percentage of the appropriated money equal to double its percentage of the state population. There are exceptions for counties getting USDA rural development grant money and Jefferson County, which is capped at its 16.9% of the state population.

Charles Helms, director of economic development for Greater Louisville Inc., expects PDI to help Kentucky communities bring more sites to market to meet a widespread demand crunch.

“The low-hanging fruit is gone, and (site selectors) are having to move to the higher branches,” Helms said. “Sites rejected three or four years ago are being taken now. I see bulldozers leveling land.”

Prospects “all want a greenfield site … that’s downtown,” he joked, meaning that everyone is seeking property that requires no time-consuming cleanup or remediation and is as close to airports and support services as possible.

Now, even suburban sites are growing difficult to find because extending infrastructure farther and farther is costly, said Helms, whose GLI work extends across a 15-county area.

Yet, the long-term prospects for more projects in Kentucky are considered rosy.

Tri-ED’s Crume sees benefit even from megaprojects going elsewhere, because they can lock up so much of the available project-support capacity of a region that smaller undertakings lose out and don’t want to locate nearby.

Additionally, he reads the funding that the Kentucky General Assembly put into HB 745 to be an indication of other strong prospects considering the state for even more megaprojects.

“There is a real battle for sites right now,” Crume said. “We don’t know what Kentucky (at the Cabinet for Economic Development level) is working on today in their pipeline, but you know that it influenced what turned around in legislation.”